C L A U D E L É V I S T R A U S S 1 9 0 8 - 2 0 0 9

INTRODUCTION

CLAUDE LÈVI-STRAUSS AND THE "EXCHANGE OF WOMEN"

Article by fil. lic. Erik Rodenborgpublished on his Website and in the pamflet; Socialisten: ”Marxism, feminism eller mittemellan” from 2011

My translation into English.

The social anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss was greatly tributed from all over the world when he celebrated his 100th birthday but nobody mentioned his extremely misogynist theories.

When the social anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss celebrated his 100th birthday he was congratulated and embraced from all over the world but nobody made any comment about his extremely misogynist ideas. He was portrayed as a great pioneer, theorist and anthropologist field worker. But as a matter of fact he represented an important part of the bourgeois backlash against the knowledge and developments made by ethnologists and ethnographers during the 19th century.

When ethnology and ethnography developed during the 19th century and material from the ”primitive” cultures from across the globe were juxtaposed, it became a great challenge to the bourgeois and patriarchal worldview. Ethnologists, christian evangelists and other field workers had stumbled into cultures which were quite different from ours and rendered new standpoints and views.

On one hand, many of these societies differed a lot from capitalism and hierarchical class-systems in a decisive way. Economically and materially they were equal and no ruling elite was parasitising on others. This kind of system was detained in most of the hunter and gatherer societies and many of the farming communities as well.

Another discovery was that women often held a stronger position in these “primitive” societies than in our western culture. In many of them descent was traced through the female line (matrilineal kinship) and not through the fathers and in some of them the males had to move into the women´s house at marriage (matrilocal settlement).

The earliest etnographs, as for example Edward Burnett Tylor, Lewis Henry Morgan, Edwin Sidney Hartland, and James Georg Frazer attempted to systemise these reviews into a bigger coherent picture of which they seeked to construct theories about social, political and religious “development”. Friedrich Engels took up the issue in his classical work: "The Origin of the Family, Private Property and State”

The most common view was similar to the one Engels pursued. Egalitarian societies were older than hierarchical and matrilineal older than patriarchical. The class society and subduing of woman were not part of he primordial conditions in the origin of human society.

This view was underpinned by a lot of data. One of the phenomena that had been noticed was that whilst many transformations from matrileneal to patrilineal kinship had been taken place during history, the opposite development never was noticed.

During the beginning of the 20th century there was a development in the opposite direction against this evolutionary perspective. The school of anthropologists around Franz Boaz in USA problematised the possibility of constructing an evolutionary line of developments. Instead one took the starting point in concrete “particular” historical sequences and meant that any further than that was not possible for the anthropologist to get. They used to be delineated as “historian particularists”. They were enormously influential.

Less influential were the extremely diffusionist theories, claiming that almost all known cultures have been spread out from Egypt or Mesopotamia.

The next step was to deny even the existence of history itself. The functionalist school ( with Malinowski and Radcliffe Brown as the prominent figures ) were of the opinion that it made no sense to reconstruct ones local historian sequenses. Instead one should focus on the social functions in the different societies. What seemed to be remnants from earlier societal conditions or religions, could in fact be explained by the function it held in the new society. The result of that carriage was to become a very static view on society, in which transformations were totally ignored.

The common view in all these schools was the universality of male dominance and the denial of the fact that there might have existed egalitarian societies.

This was approximately what the picture looked like when Claude Lévi Strauss and his structuralist school entranced the scene. Lévi-Strauss, didn't just ignore history, he ignored in principle society as a whole. That, he claimed, was motivated (by using marxism as a fashionable excuse) of his attempt to create an anthropology for the superstructure and thereby admitted that he consciously ignored the economical and social base. Instead he focused on what he believed was universal features in the thinking of man, which might explain myths, religions, social interrelatedness and systems of kinships.

Among other things, this ended up in vastly speculative ideas about the origin of myths and fairytales. The foundation of his theory was the idea that the thinking of man always were built upon binary oppositions. This idea had some similarities to Hegel´s dialectic´, with the difference, though, that it didn´t encompass the idea of transformation. A static pseudo-dialectic, in which everything might be viewed as eternal thesis's and antithesis's in the thinking. Mostly the result was beyond comprehension and Lévi-Strauss then distanced himself from all his followers by declaring that the had misinterpreted him. The most plausible explanation to that might be that it simply was impossible to understand his system as the complete foundation was incomprehensible.

In one sense, though, he was quite comprehensible. He claimed that the origin of society was built on “the exchange of women”. He developed this idea in his most famous book: “The Elementary Structure of Kinship“ from 1949. ( published for free on the net)

In one sense, though, he was quite comprehensible. He claimed that the origin of society was built on “the exchange of women”. He developed this idea in his most famous book: “The Elementary Structure of Kinship“ from 1949. ( published for free on the net)

The fundamental base for this idea was as follows; For the culture to emerge, groups of men must start to exchange women between themselves. This development was initiated by the establishment of the incest taboo. That implied to Lévi-Strauss that the men, instead of keeping all the women to themselves, gave them away to other men.

The reason to this was the “deep polygam tendencies, that´s prevailing in all men." (Lévi-Strauss 1969:38) This resulted in a constant scarcity of available women, they were never plenty enough. In addition the most desirable women always were in minority. (1969:38) By exchanging women with other groups the available women could increase.

The human society is always, according to Lévi-Strauss “at first hand a masculine society”. (Lévi-Strauss quoted in Leacock 1981:232).

≈

Now, it was not only women who were exchanged between the men, but as the women were “the most precious possesions” (1969:232) the exchange of them became the most fundamental in all human societies.

It should not be denied, though, that there are patriarchal, patrilineal and patrilocal societies in which marriage and the system of kinship to some extent might be described in the way Lévi-Strauss does. But as an anthropologist he would have been aware of the existence of many societies in which his scheme didn´t / don´t fit in whatsoever. How did he relate to them? Societies being matrilineal and matrilocal in which it was the men who were “exchanged” between different mother, he seems to have simply ignored. He writes: “the total relationship of exchange which constitutes marriage is not established between a man and a woman… but between two groups of men, and the woman figures as only one of the objects in the exchange, not as one of the partners between whom the exchange take place…” (1969:115). Thus, he claims this being a universal in every culture.

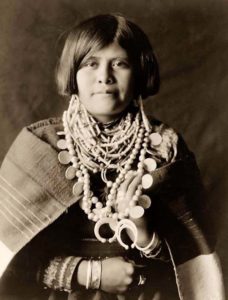

One might compare Lévi-Strauss with the Jesuit missionary Lafitau,

who in the 18th century wrote about the position held by the women among the matrilineal and matrilocal iroquois people:

“Nothing, however, is more real than this superiority of the women. It is of them that the nation really consists; and its through them that the nobility of the blood, the genealogical tree and the facilities are purpetuated. All real authority is vested in them. The land, the fields and their harvest all belong to them. They are the souls of the Councils, the arbiters of peace and war. The have charge of the public treasury." (quoted from Leacock 1981:239)

Its hard to imagine these women accepting being passively exchanged between “groups of men”. That wasn´t either the case. As in all matrilineal-matrilocal systems it was the man who had to move home to the woman´s clan by marriage. He wasn´t even allowed to become a member in the group of kinship of the woman, but the children of the man and the woman were to become a part of the clan of the mother. By divorce the man had to move away from the woman, and the children stayed with her.

And divorce is very easy to get. If a woman wants to get a divorce from her husband she just has to put his moccasins outside the door. Then he has to collect his belongings and leave.

(My adding: Quoting Lewis Morgan (1965: 65-66):"No matter how many children, or whatever goods he might have in the house, he might at any time be ordered to pick up his blanket and budge and after such orders it would not be healthful for him to disobey; the house would be too hot for him; and unless the intercession of some aunt or grandmother, he must leave to his own clan.")

Now someone might argue that the Iroquois people was an exception. Yes maybe in some respects, but not in this. In all matrilineal - matrilocal systems the same rules were prevailing. In North America could be mentioned the Hopi -and Zuni-indians, who detained the same system.

But even in the matrilineal systems detaining patrilocal settlement it would be absurd to apply Lévi-Strauss scheme. Certainly the woman therein had to move to the husband; not the other way around, but it was always easy to get divorced without any hassle, and when the woman got divorced she moved back to her clan - together with the children who belonged to her.

Many hunter and gatherer societies lack matrilineal kinship, but their system of kinship are often blurry, and divorce a natural right, and most marriages lasts only for shorter periods. It seems unreasonable that either men nor women would detain the notion of women being exchanged between groups off men.

Claude Lévi-Strauss´ theories supposedly tell more about his own twisted mind than about what kind of kinship ”primitive” peoples detain. That they have grown so popular, although their empirical foundations are nearly non-existent and over and over again have been demolished by vicious critics, says something not only about Lévi-Strauss. It says something about the patriarchal society in which the twisted mind of Lévi-Strauss is elevated to a male chauvinist academic ”truth”.

Recommended literature and reference:

Eleanor Burke Leacock: Myths of Male Dominance, 1981

Reference: Claude Lévi-Strauss: The Elementary Structures of Kinship, Boston 1969 (1949)

Erik Rodenborg december 2008